Aviva Ben-Ur and Rachel Frankel

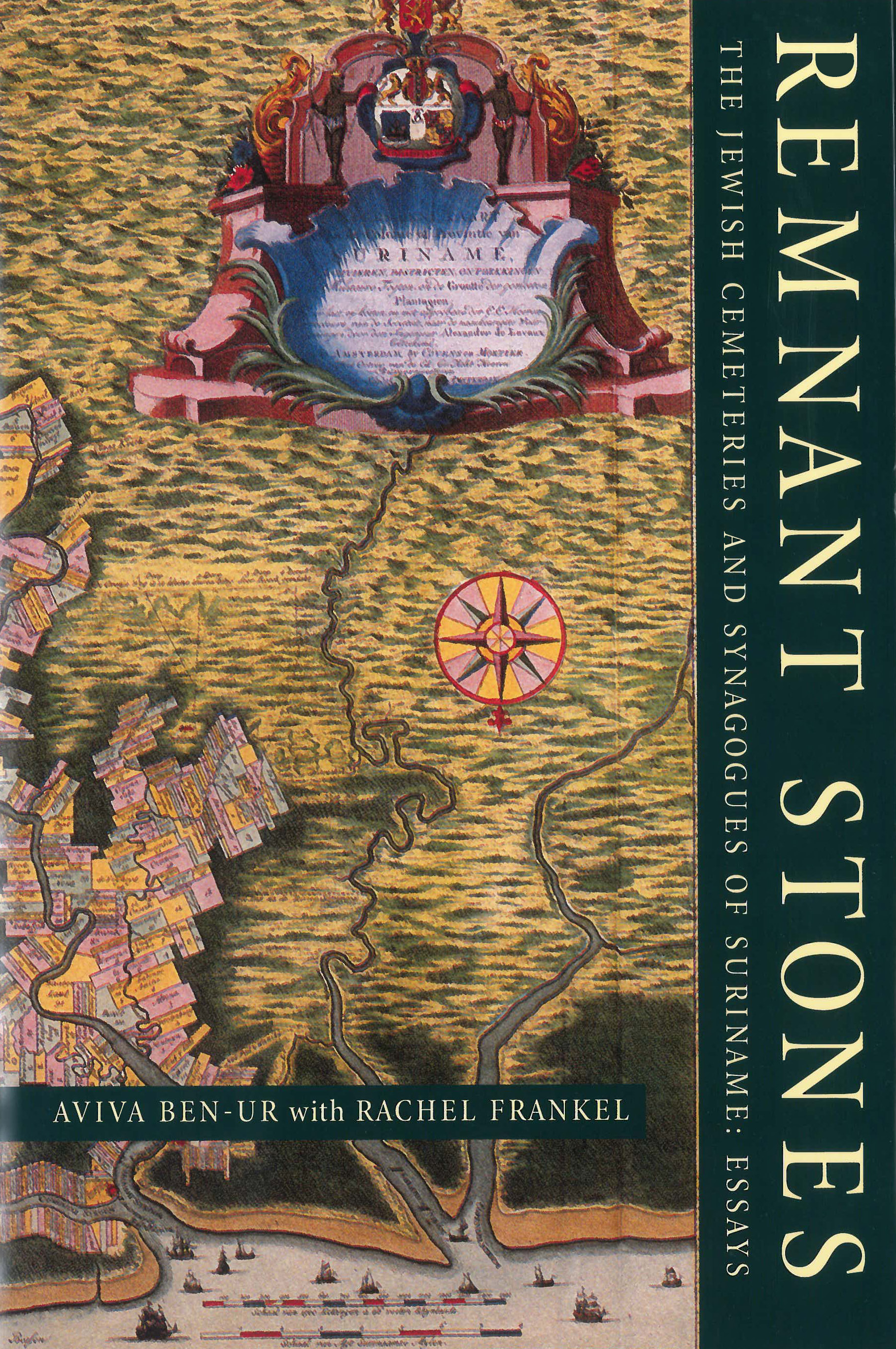

In the 1660s, Jews of Iberian ancestry, many of them fleeing Inquisitorial persecution, established an agrarian settlement in the midst of the Surinamese tropics. The heart of this community—Jodensavanne, or Jews’ Savannah—became an autonomous village with its own Jewish institutions, including a majestic synagogue consecrated in 1685. Situated along the Suriname River, some fifty kilometers south of the capital city of Paramaribo, Jodensavanne was by the mid-eighteenth century surrounded by dozens of Jewish plantations sprawling north- and southward and dominating the stretch of the river. These Sephardi-owned plots, mostly devoted to the cultivation and processing of sugar, carried out primarily by enslaved Africans, collectively formed the largest Jewish agricultural community in the world at the time and the only Jewish settlement in the Americas granted virtual self-rule.

Sephardi settlement paved the way for the influx of hundreds of Ashkenazi Jews, who began to emigrate in the late seventeenth century from western and central Europe. Generally banned from Jodensavanne, these newcomers settled in Paramaribo, where they established their own cemeteries and historic synagogue. Meanwhile, slave rebellions, Maroon attacks, the general collapse of Suriname’s economy, soil depletion, absentee land ownership, and a ravaging fire all contributed to the demise of the old Savannah settlement beginning in the second half of the eighteenth century.

Remnant Stones details three Sephardi Jewish cemeteries, whose monuments date from 1666 to 1904; one Ashkenazi cemetery, whose monuments date from the 1680s to the late nineteenth century; the Creole (Afro-Surinamese) cemetery in Jodensavanne, dating to the late nineteenth century at the latest; and the remains of a seventeenth-century synagogue in the heart of Jodensavanne.

This volume of essays offers a historical and cultural overview of Suriname’s Jewish community, with special emphasis on its synagogues and the Jewish and Creole cemeteries. It complements the first volume, Remnant Stones: The Jewish Cemeteries of Suriname: Epitaphs, which presents transcriptions, English translations, annotations, and selected photographs of nearly 1,700 gravestones, accompanied by scaled plans of the cemeteries.

[T]his volume should be considered necessary reading in any serious course on American Jewish history – Laura Leibman, Reed College

Aviva Ben-Ur is Associate Professor in the Department of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Massachussetts Amherst. Rachel Frankel is an architect in New York, where she has had her own practice since 1996.